1946 COLUMBIA RACE RIOT

The 1946 Columbia Race Riot stands as a pivotal moment in our community’s history, one that not only transformed Columbia but also sent shockwaves across the nation. Surprisingly, the full story of this significant chapter remains relatively unknown to many Columbia residents, even lifelong ones.

At CPJI, our mission is centered on unearthing and sharing the truth behind the events of 1946. We believe that sharing the truth of this history is essential to understanding its impact on our present day. By telling this story, we aim to not only acknowledge the injustice and tragedy of what transpired that day but also honor the heroes of the day and what they endured.

Moreover, we firmly believe that redemption can be found in embracing this story as a community and collectively working towards a better future.

Why “Race Riot” is Misleading

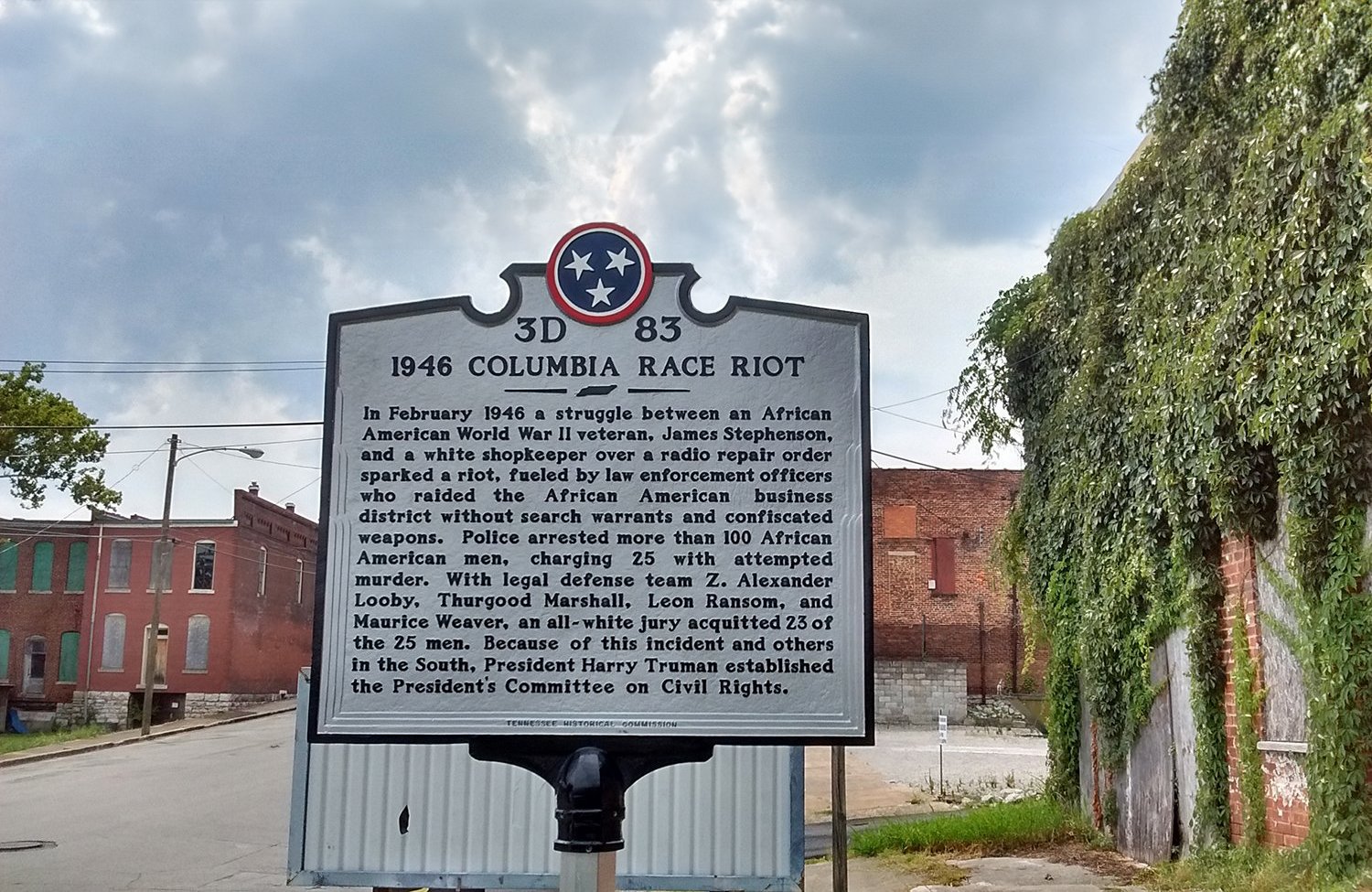

Historically, the events of 1946 have been known as the Columbia “race riot” which implicated black residents, but the majority of the rioting on February 26, 1946 was done by members of law enforcement and others.

WHAT IS THE STORY OF THE 1946 COLUMBIA RACE RIOT?

The African American Heritage Society of Maury County worked to have a historical marker placed at 115 East Eighth Street — near the A. J. Morton Funeral Home — recognizing the events of 1946.

On the morning of February 24, 1946, James Stephenson, a young Black Navy veteran just home from service, and his mother, Gladys, were trying to pick up their radio from the department store Castner Knott, where it was being repaired. There had been a mix-up with the radio, and the store had sold it to another person. They got it back, but it was now going to cost Gladys Stephenson much more than expected. Gladys Stephenson got into an argument with Billy Fleming, the store clerk. James Stephenson intervened and ushered her out the door. On the way out, she loudly said, “I will take my radio someplace else to get it fixed because all they did here was tear it up.” Fleming again confronted Gladys Stephenson, and James Stephenson stepped in between.

As they turned to leave, Fleming ran down the stairs and punched James Stephenson in the back of the head for "looking at him in a threatening manner." James Stephenson, who was a welterweight boxer in the Navy, turned around and threw a series of punches at Fleming, knocking him through the plate glass window onto Columbia Square. The police soon arrived, and the Stephensons were arrested and charged with street fighting, fined $50, and transferred to the county jail under the care of Sheriff J.J. Underwood. However, Billy’s father got those charges ramped up to attempted murder.

Soon, a white mob had formed on Columbia’s square and rumors of rope being purchased and lynching were spread. Columbia’s Black residents didn’t take the rumor lightly. Sol Blair and James Morton, two prominent black businessman and leaders of the black community, gathered up enough money to post bail for the Stephensons. They took James Stephenson back to the Bottom.

Gladys Stephenson

James Stephenson

Sheriff Underwood, worried about the mob, drove down to the Bottom and visited with Blair and James Morton. He urged them to get James Stephenson out of town and tried to disperse the mob at the square, but the tension was rising. Black residents on East 8th Street, led by World War II veterans, began to arm themselves, took up positions on the roof, and shot out the streetlights. These veterans had fought for freedom abroad during WWII, only to come home and face more overt racism in their hometown. They would not stand for it this time.

Eventually, Columbia Police Chief Walter Griffin decided to take some officers and go down to East 8th Street to sort things out. Residents in the area saw four armed law enforcement officers walking down the street and told them to stop advancing. They continued to enter the area when someone yelled "fire," and the officers were fired upon. Each was hit with buckshot, but none were seriously injured.

Walter Griffin

Lynn Bomar

Sheriff Underwood then called Governor Jim Nance McCord for assistance.

The governor dispatched Lynn Bomar, head of the Tennessee Highway Patrol, to Columbia. Bomar arrived with 60-70 troopers and immediately deputized civilians on the square, urging them to go to the Armory and gather weapons. The director of the Armory refused to arm the citizens and called General McGavock Dickinson with the Tennessee State Guard.

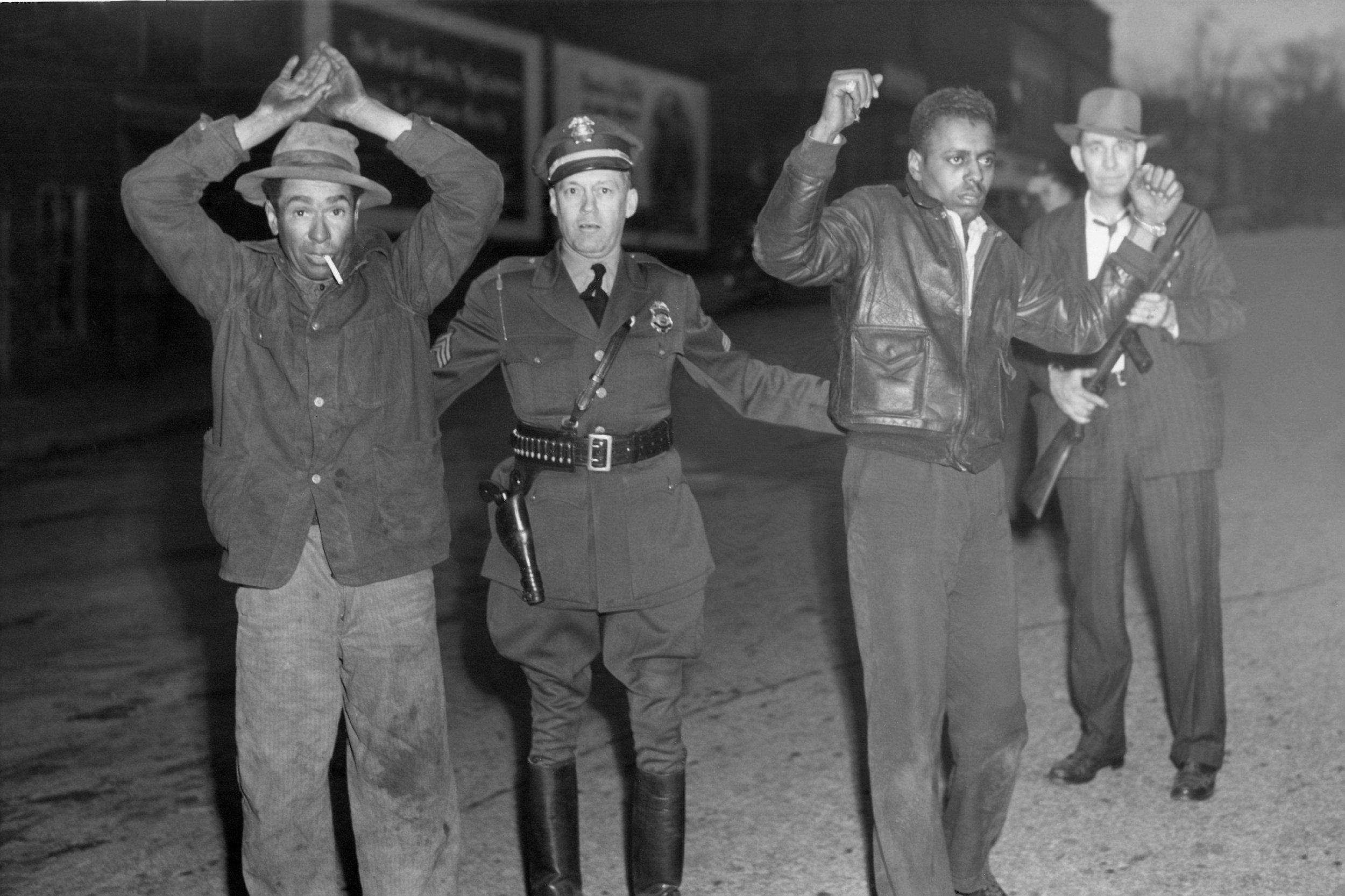

General Dickinson arrived in Columbia later that night with 900+ guardsmen. By now there were fewer than 150 people gathered in the Bottom, most of them dispersing after the officers were fired upon. General Dickinson decided it best to wait until morning and end the conflict with a show of force. However, Bomar and the Tennessee Highway Patrol had other ideas. They went into the Bottom at dawn and destroyed the entire district. They ransacked businesses, and many people were badly beaten or shot. More than 100 people were arrested and marched through the streets before the Tennessee State Guard had arrived. This act devastated Columbia’s Black business district.

As officers raided the Morton Funeral Home, Mary Morton — wife of James Morton — called the NAACP, and they dispatched Maurice Weaver, Z. Alexander Looby, Walter White, Leon Ransom, and Thurgood Marshall to defend those charged. Of the 100 arrested, two were killed in police custody for allegedly reaching for weapons in a crowded interrogation room. They were being questioned in a room full of confiscated weapons and, inexplicably, left alone. They died en route to Meharry Hospital in Nashville because the local hospital would not treat Blacks.

James Morton

Sol Blair

Eventually, 26 people were charged with attempted murder or accessory to attempted murder, including local business leaders James Morton, Sol Blair, and other local leaders like Rev. Calvin Lockridge. One of the 26 charged later died of pneumonia while in custody.

Of the 25 men brought to trial, all but two were acquitted by an all-white jury in Lawrenceburg, Tenn., where the trial was moved to at the request of the defense because in 1946 it had been 50 years since a Black person had sat on a jury in Columbia. The 23 were acquitted for lack of evidence, and the other two were charged on lesser counts.

Charges against the Stephensons were quietly dropped after the trial, and neither ever returned to Columbia. Instead, they lived the rest of their lives in Detroit and Chicago.

Watch this video to hear from James Stephenson himself about the events of 1946.

Video courtesy of Bridgett Stuart

THE ROLE OF THE COLUMBIA RACE RIOT IN CIVIL RIGHTS HISTORY

The events of February 1946 turned the tide against violence and segregation both locally and nationally. The brave statement from Columbia’s Black community — that there would be “no more social lynchings” — resounded in Washington, D.C., and helped usher in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ‘60s.

The events caught the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt, U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark and even President Harry S. Truman, who was inspired, in response to the Columbia uprising and other violence against African Americans, to issue Executive Order 9808 forming the President’s Committee on Civil Rights.

The committee’s findings led to a series of orders that in effect began the Civil Rights Movement, including desegregation of the federal workforce, desegregation of the U.S. armed forces, establishment of a permanent civil rights division, abolishment of poll taxes, and protections against lynching. These laws helped lay the groundwork for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act in 1965.

THURGOOD MARSHALL’S ALMOST LYNCHING IN COLUMBIA

Thurgood Marshall was in his late 30s when he was sent to Columbia by the NAACP to defend the 25 individuals who went on trial for the events of the 1946 uprising. A bout of pneumonia, however, would sideline Marshall for most of the trials in Lawrenceburg, but he returned to Columbia in November 1946 to defend the two final individuals on appeal.

Following the successful trial, Marshall got in a car with his fellow lawyers Walter White, Z. Alexander Looby, and reporter from The Daily Worker named Harry Raymond. Marshall was driving as they crossed Duck River bridge on Nashville Highway when three police cars pulled them over. The cars contained a mixture of uniformed officers and civilians, all with guns. They arrested Marshall for drunk driving and loaded him in a police car. However, the car did not take him to the courthouse. Instead, it turned down a dirt road where even more were gathered.

Ignoring orders to continue on to Nashville, Looby jumped in the driver’s seat and followed the police car. That action, and the action of local African Americans like WWII veteran Milton Murray, saved Marshall’s life that day. They confronted the lynch mob on the banks of the river and the officers decided to take Marshall to Magistrate Jim Pogue. Pogue gave Marshall a breathalyzer test, asking him to breathe on him because Pogue was a tee-totaler and could “smell liquor a mile away.” He said, “he ain’t been drinking fellas, let him go.”

Marshall and his fellow travelers arranged to make the trip back to Nashville, but Looby didn’t trust the police. He arranged for a decoy car to drive down Nashville Highway while the car carrying Marshall went out of town by another route. Sure enough, the decoy car was again pulled over by the police on Nashville Highway. Once the police discovered Marshall was not in the car, the driver was beaten badly, but Marshall escaped.

After Columbia, Marshall would go on to build a distinguished career as a civil rights attorney, arguing such cases as Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court. In 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Marshall as the first African American to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. Interestingly enough, President Johnson’s appointment occurred just months after he himself visited Columbia to dedicate Columbia State Community College. As he was leaving town, President Johnson drove over the same bridge on the Duck River where Marshall was arrested.

What happened in Columbia would always stay with Marshall. He once said in an interview that he had never been more scared for his life than he was in Columbia.

RESOURCES

Below is a list of resources that helped in our research of the events of 1946. Explore them all to learn more and gather insights from experts, journalists and academics.

-

Lynching & Frame-Up in Tennessee; Robert Minor (1946)

South of Freedom; Carl T. Rowan (1952)

No More Social Lynchings; Robert W. Ikard (1997; out of print)

The Color of the Law: Race, Violence, and Justice in the Post-World War II South; Gail Williams O’Brien (1999)

The Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America; Gilbert King (2012) -

Civil Rights: Columbia Race Riot; Tennessee State Museum — American Radio WorksTennessee 4 Me

Columbia Race Riots; American Radio Works

Columbia (Tenn) Race Riot — Research Material, 1946-1996; Gail Williams O’Brien; Tennessee State Library and Archives

Columbia Race Riot, 1946; The Tennessee Encyclopedia

Races: The Mink Slide: The Aftermath (1946); Time Magazine

Race Riot In Columbia, Tennessee February 25-27, 1946; Tennessee Historical Quarterly

Two Tennessee riots made news after World War II;; The Tennessee Magazine

Dark Days in Columbia History;; Columbia Daily Herald

Self-Defense, Subversion and the Status Quo: Four Tennessee Newspapers Asses the Columbia Race Riot of 1946 by Landon Woodruff (2018); University of Missouri-Columbia – M.A. Thesis Paper

The Columbia Race Riot (1946); BlackPast

Thurgood Marshall in Tennessee: His Defense Of Accused Rioters; His Near-Miss with a Lynch Mob – by David Hudson (2020); Tennessee Bar Journal

'Mink Slide uprising' in Columbia is history white people should study to understand the present; The Tennessean

How a 1946 dispute over a broken radio in Tennessee helped spark the civil rights movement; USA Today

America’s first post-World War II race riot led to the near-lynching of Thurgood Marshall; The Washington Post -

Columbia 1946: Riot or Rising?: An Interview with Trent Ogilvie and Russ Adcox; Middle Tennessee Backyard History (2021)

Reconciliation to Revitalization: The 75th Anniversary of the Columbia Race Riot; Stand Together Fellowship (2021)

Milton Murray Discusses Thurgood Marshall in Columbia, TN 1946; Albert Gore Research Center (2017)

The Hidden History of the Quest for Civil Rights: 1946 Columbia Race Riot; Emory University (2012)

Thurgood Marshall: A Life in American History; Virginia Museum of History & Culture (2019)

-

1946 Columbia Race Riot; Black Authors Audiobooks Podcast (2022)

The Columbia Race Riot of 1946, Part 1; History’s Hook hosted by Tom Price (2021)

The Columbia Race Riot of 1946, Part 2; History’s Hook hosted by Tom Price (2021)

Columbia TN, Race Riots 1946; The Melanated Power Hour (2020)

Interview with Dr. Carol Anderson: 1946 Columbia, TN Race Riots & The Myth of Black American Cowardice; People Activity Radio (2019)